Understanding the Screening of a Static Magnetic Field in Superconductors

Introduction

One of superconductor’s intriguing properties is the ability to screen or expel magnetic fields, a phenomenon known as the Meissner effect. This post aims to delve into the mathematical underpinnings of this effect, using the London equations as a starting point.

The London Equations

The London equations are a pair of equations that describe the electromagnetic behavior of superconductors. The equations are as follows:

\begin{equation} \textbf{E} = \frac{\partial}{\partial t} (\Lambda \textbf{J}_s), \tag{1} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \textbf{h} = -c \text{curl} (\Lambda \textbf{J}_s), \tag{2} \end{equation}

In these equations, $\textbf{E}$ represents the electric field, $\textbf{J}_s$ is the superconducting current density, $\Lambda$ is the London penetration depth, $\mathbf{h}$ is the magnetic field, and $c$ is the speed of light.

From these two equations, we can derive a third equation:

\begin{equation} - \nabla \times \nabla \times \mathbf{E} = \nabla ^2 \mathbf{E} = \mathbf{E} / \lambda^2, \tag{3} \end{equation}

This equation shows that the electric field $\mathbf{E}$ is inversely proportional to the square of the penetration depth $\lambda^2$. Similarly, we can derive a fourth equation for the magnetic field:

\begin{equation} \nabla ^2 \mathbf{h} = (1/\lambda^2) \mathbf{h}, \tag{4} \end{equation}

Penetration Depth and Screening

The penetration depth $\lambda$ is a critical parameter in understanding the screening of electromagnetic fields in superconductors. It is given by the equation:

\begin{equation} \lambda^2 = mc^2 / 4 \pi n_s e^2, \tag{5} \end{equation}

In this equation, $m$ is the mass of the electron, $c$ is the speed of light, $n_s$ is the density of superconducting electrons, and $e$ is the charge of the electron. The penetration depth $\lambda$ describes how far an external magnetic field can penetrate into a superconductor.

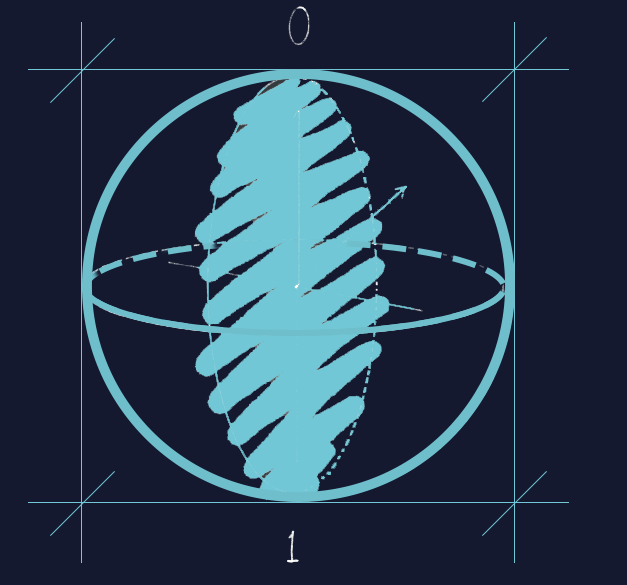

A particular solution of Equation (4) describes a magnetic field $h$, parallel to the surface, which decreases exponentially into the interior of a bulk superconductor as:

\begin{equation} h(x) = h(0) e^{-x/\lambda}, \tag{6} \end{equation}

Here, $x$ is the distance measured from the surface. This equation shows that the magnetic field decreases exponentially as we move into the superconductor, effectively being “screened” from the interior.

The Impact of Temperature

The penetration depth $\lambda$ is not constant but varies with temperature. As the temperature approaches the critical temperature $T_c$ at which the material becomes superconducting, the density of superconducting electrons $n_s$ tends to zero, causing $\lambda(T)$ to diverge. This temperature dependence is often modeled by the equation:

\begin{equation} \lambda(T) \approx \lambda(0)/(1-t^4)^{1/2}, \tag{7} \end{equation}

Here, $t = T/T_c$ is the reduced temperature, and $\lambda(0)$ is the penetration depth at absolute zero temperature. This equation suggests that as the temperature approaches the critical temperature, the penetration depth increases, meaning the magnetic field can penetrate further into the superconductor.

The Case of a Flat Superconducting Slab

To illustrate the application of the London equations, let’s consider a flat superconducting slab of finite thickness $d$ in an applied parallel magnetic field $H_a$. Solving Equation (4) with the boundary conditions that $h=H_a$ at the two surfaces at $x = \pm d/2$, we obtain:

\begin{equation} h = H_a \frac{\cosh{(x/\lambda)}}{\cosh{(d/2\lambda)}}, \tag{8} \end{equation}

This equation shows that the magnetic field $h$ is reduced to a minimum value at the midplane of the slab. Averaged over the sample thickness $d$, we find:

\begin{equation} B \equiv \overline{h} \equiv H_a + 4 \pi M = H_a \frac{2 \lambda}{d} \tanh{\frac{d}{2\lambda}}, \tag{9} \end{equation}

Here, $B$ is the average magnetic field, and $M$ is the magnetization of the superconductor. This equation shows that the average magnetic field $B$ decreases as the thickness $d$ of the slab increases.

The Case of a Thin Film

\begin{equation} M \rightarrow -(H_a / 4\pi) (d^2/12\lambda^2), \tag{10} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} (F_n - F_s) \vert_{H=0} = - \int_0^{H_m} M(H) dH, \tag{11} \end{equation}

For a thin film that is parallel to the applied field, we insert Equation (10) into Equation (11), and see that the critical field is increased from $H_c$ to

\begin{equation} H_{c \Vert} = \sqrt{12}H_c \lambda / d, \tag{12} \end{equation}

In the realm of superconductivity, the Ginzburg-Landau (GL) theory offers a more comprehensive understanding of the behavior of superconductors. One of the intriguing phenomena it elucidates pertains to the critical magnetic field of thin superconducting films.

Consider, for instance, a thin film of tin with a thickness of approximately 100 $\unicode{xC5}$. This film exhibits a penetration depth, denoted as $\lambda$, of approximately 500 $\unicode{xC5}$ and a critical magnetic field, denoted as $H_c$, of around 300 Oersted (Oe). According to the GL theory, when this film is subjected to a magnetic field parallel to its surface, the critical magnetic field experiences a substantial increase, reaching values in the vicinity of 7,500 Oe. This is a significant deviation from the initial critical field.

The underlying reason for this phenomenon is the reduction in the film’s magnetization, denoted as $M$, in the superconducting state. Specifically, the magnetization of the film is greatly diminished below the Meissner value, which is a characteristic property of superconductors that signifies their ability to expel magnetic fields. This reduction in magnetization is a primary factor contributing to the marked increase in the critical magnetic field.

The Case of Wire

In the study of superconductivity, the behavior of superconducting wires under the influence of an electric current is a topic of considerable interest. A parameter that signifies the maximum current the wire can carry without losing its superconducting state.

Consider a long superconducting wire with a circular cross-section and a radius significantly larger than the penetration depth, denoted as $\lambda$. When this wire carries a current, denoted as $I$, it generates a circumferential self-field at its surface. The magnitude of this self-field, denoted as $H$, is given by the equation $H = 2I/ca$.

The Silsbee criterion stipulates that when this self-field reaches the critical field, denoted as $H_c$, superconductivity in the wire will be destroyed. Consequently, the critical current, denoted as $I_c$, can be defined as $I_c = ca H_c/2$. Interestingly, this critical current scales with the perimeter of the wire, not its cross-sectional area, suggesting that the current flows only in a surface layer of constant thickness.

Analytical application of the London and Maxwell equations confirms this hypothesis, indicating that the thickness of this surface layer is indeed λ. Given that the cross-sectional area of this surface layer is $2 \pi a \lambda$, the critical current density, denoted as $J_c$, can be expressed as $J_c = I_c / 2 \pi a \lambda$. This relationship can be further simplified to $J_c = c/4 \pi H_c/\lambda$.

While this argument is based on the critical field, more general energetic arguments suggest that this value of $J_c$ also holds for wires that are much thinner than $\lambda$. In such cases, the current density is nearly uniform, and $I_c$ is proportional to the cross-sectional area of the wire. The full Ginzburg-Landau theory, however, modifies this result by a numerical factor of $(2/3)^(3/2)$, which is approximately 0.5.

For typical numerical values of $H_c = 500 Oe$ and $\lambda = 500 \unicode{xC5}$, the critical current density $J_c$ is found to be of the order of $10^8 A/cm^2$, a remarkably large value. This finding underscores the extraordinary electrical properties of superconducting wires and their potential for high-current applications.

Reference

- Tinkham, M. Introduction to superconductivity. (Dover Publications, 2015).

Leave a comment