The London Equation

The London Equations

London Eqation. Now, we know that trying to derive these equations classically, using electrons with an infinite mean free path, isn’t exactly rigorous. But it does give us a good feel for what’s going on, so we’re going to use it to get a handle on these equations and figure out the penetration depth $\lambda$.

First up, we’ve got the Drude model for electrical conductivity. This is where we apply classical mechanics to electron motion, and we get this equation:

\begin{equation} m \frac{dv}{dt} = e\mathbf{E} - \frac{mv}{\tau} \end{equation}

Now, if we imagine that a certain density $n_s$ of a superconductor’s electrons act like there’s no scattering (by letting their $\tau_s$ go to infinity), we can replace Ohm’s law with an accelerative supercurrent.

In the case of superconductivity, $\tau_s$ is used to describe the time it would take for the superconducting electrons to return to equilibrium (i.e., stop moving) after being disturbed, if there were any scattering or resistance. However, in a perfect superconductor, there is no scattering or resistance, so $\tau_s$ is considered to be infinite. This leads to the phenomenon of persistent current, a key feature of superconductivity, where the electric current continues to flow indefinitely without any applied voltage.

This gives us:

\begin{equation} \frac{d J_s}{dt} = \frac{n_s e^2}{m} \mathbf{E} = \frac{\mathbf{E}}{\Lambda} = \frac{c^2}{4 \pi \lambda^2} \mathbf{E} , \tag{1} \end{equation}

This is basically the first London equation:

\begin{equation} \mathbf{E} = \frac{\partial}{\partial t}(\Lambda J_s) , \tag{2} \end{equation}

And we can define $\Lambda$ and $\lambda$ like this:

\begin{equation} \Lambda = \frac{4 \pi \lambda^2}{c^2} = \frac{m}{n_s e^2} , \tag{3} \end{equation}

The second London equation is all about how magnetic fields get screened, even if they’re not changing with time. This is super important for understanding the Meissner effect. Here’s the equation:

\begin{equation} h = -c \text{curl}(\Lambda J_s) , \tag{4} \end{equation}

And if we use Maxwell’s equations, we can see that:

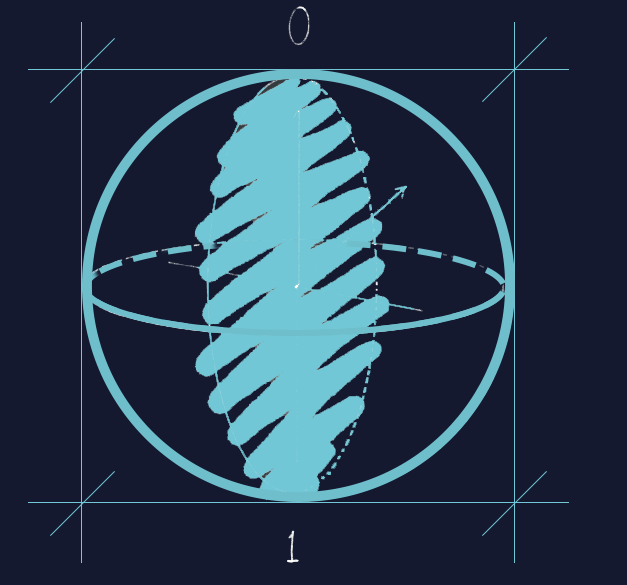

\begin{equation} \nabla^2 h = \frac{1}{\lambda^2}h , \tag{5} \end{equation}

And we can define $\lambda$ like this:

\begin{equation} \lambda^2 = \frac{mc^2}{4 \pi n_s e^2} , \tag{6} \end{equation}

So, equations (5) and (6) give us a way to define the superconducting electron density $n_s$ in terms of something we can actually measure, $\lambda$.

Reference

- Tinkham, M. Introduction to superconductivity. (Dover Publications, 2015).

Leave a comment