Electromagnetic Cavity Modes

In the realm of classical electrodynamics, Maxwell’s equations serve as the cornerstone for describing the electromagnetic mode of a cavity. However, when we transition to the quantum mechanics perspective, the narrative changes. Here, the focus shifts to the quantization of the electromagnetic field within a real cavity, particularly a one-dimensional one.

The process of quantizing the electromagnetic field is a complex one. It involves solving Maxwell’s equations within a specific set of boundary conditions. This solution then allows us to identify a corresponding canonical position and momentum. These are then promoted to operators, marking a significant step in the quantization process.

Inside a cavity with perfectly conducting walls, the electric and magnetic fields can be described by a solution that involves a wave number corresponding to the frequency. This solution provides a comprehensive understanding of the electromagnetic behavior within the cavity.

The energy of an electromagnetic mode within the cavity bears a striking resemblance to the energy of a classical harmonic oscillator. Each mode, in essence, behaves as a quantum harmonic oscillator, adding another layer of complexity to the quantum narrative.

\[\hat{H} = \frac{1}{2}[\hat{p}^2(t) + \omega^2_c \hat{q}^2(t)]\]Here, $\omega_c = \frac{k}{\sqrt{\mu_0 \epsilon_0}}$, while $k= m \pi/L$, $m=1,2, \dots$ and $L$ is distance. $q(t)$ is time-evolution for modees and has dimension of length, while $p(t) = \dot{q}(t)$, and these canonical position and momentum treat the Hamiltonian quantum mechanically by promoting themselves to operators $\hat{p}$, and $\hat{q}$.

To describe the state of the cavity, we must solve the corresponding eigenvalue problem. Considering Hamiltonian

\[\hat{H} = \omega_c (\hat{a}^{\dagger}\hat{a} + \frac{1}{2}) = \omega_c(\hat{n} + \frac{1}{2})\]we have

\[\hat{H} \vert n \rangle = E_n \vert n \rangle, \quad n = 0,1,2, \dots\]The photon-number $\vert n \rangle$ states derived from this solution form a complete basis that can describe any arbitrary state of the cavity.

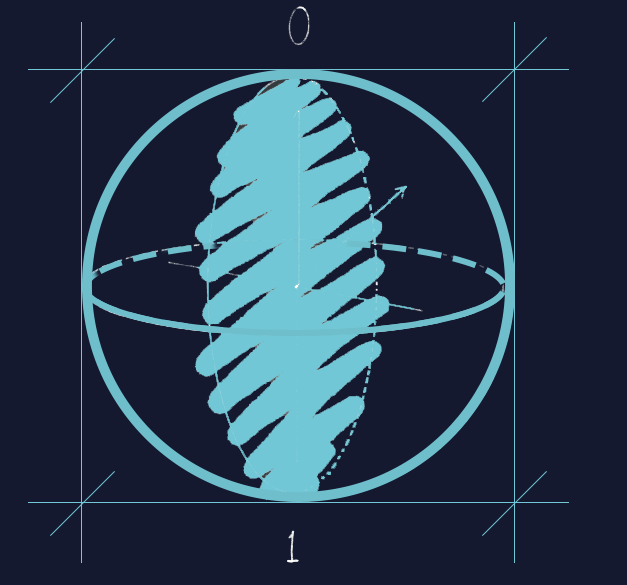

Wigner Function

The Wigner function serves as a popular tool for visualizing the state of light. While it provides an intuitive distribution for classical light, its interpretation becomes less straightforward for non-classical light. The Wigner function for given pure state $\vert \psi\rangle$ in the canonical position bassi $\vert q \rangle$.

\[W(q,p) = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} \langle q + x/2 \vert \psi \rangle \langle \psi \vert q - x / 2 \rangle e^{+ipx} dx\]Fock states, characterized by zero electric and magnetic fields, exhibit non-zero field fluctuations due to vacuum energy.

\[\vert \psi \rangle = \vert n \rangle\]These states are eigenstates of the harmonic oscillator Hamiltonian and have operational relations for photon creation and annihilation.

The Wigner function also plays a crucial role in visualizing the probability distribution of photon-number states. Interestingly, the presence of negative probabilities within the Wigner function indicates non-classical states.

The discussion extends to the calculation of the average number of photons in a cavity containing a superposition of two Fock states. It also delves into the concept of coherent states and their photon number distributions. For example, the Wigner function for the state $\vert 0 \rangle$ and $\vert 1 \rangle$ has following form.

\[\begin{aligned} \vert 0 \rangle &\rightarrow W_0(q,p) = \frac{1}{2\pi} e^{-(q^2 + p^2)} \\ \vert 1 \rangle &\rightarrow W_1(q,p) = \frac{1}{2\pi} (2q^2 + 2p^2 - 1) e^{-(q^2 + p^2)} \end{aligned}\]The central limit theorem for a Poisson distribution elucidates why the photon number distribution for a coherent state with a higher average number of photons resembles a Gaussian distribution. As the limit $\alpha$ approaches 1, the photon distribution can converges to a Gaussian distribution centered at $\vert \alpha \vert^2$ with a variance of $\vert \alpha \vert^2$.

Coherent Light

Although a coherent state is not an eigenstate of the Hamiltonian, its time evolution manifests as a rotation in phase space. Coherent states maintain their coherence under time evolution but acquire a phase. The coherent state can be represneted in the photon-number basis as

\[\vert \psi \rangle = \vert \alpha \rangle = \sum_n c_n \vert n \rangle, \quad c_n = e^{-\vert \alpha \vert^2 / 2} \frac{\alpha^n}{\sqrt{n!}}\]where $c_n$ indicates the contribution of each photon-number state in the coherent state.

Coherent light is considered classical because its behavior mirrors classical oscillatory motion and exhibits minimum quantum fluctuations. This characteristic makes it a key player in the realm of quantum mechanics.

Coherent states play a pivotal role in quantum measurement, especially in the precise measurement of the phase of a coherent signal. The Wigner function for a coherent state is a displaced vacuum Wigner function in phase space by an amount alpha.

\[\vert \alpha \rangle \rightarrow W_{\alpha}(q,p) = \frac{1}{2\pi} \exp(-(q-\mathcal{R}[\alpha])^2 - (p-\mathcal{I}[\alpha])^2)\]where $\mathcal{R}[\alpha]$ and $\mathcal{I}[\alpha]$ are the real and imaginary part of $\alpha$.

This function resembles the classical “phasor diagram” of a noisy signal, but the noise in each quadrature is quantum noise.

Reference

- Naghiloo, M. Introduction to Experimental Quantum Measurement with Superconducting Qubits. arXiv (2019). doi: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1904.09291

Leave a comment