Background

The execution of quantum algorithms on near-term devices often involves a shallow quantum circuit that is followed by sampling the measurement of an observable. When the circuit is executed, the output is a superposition of several possible states, and measuring an observable collapses this superposition into a single state. By repeating this process multiple times and gathering statistics on the outcomes, we can estimate the expectation value of the observable. This method is preferred for near-term devices because proper quantum error correction is not yet available, and noise parameters such as coherence time limit the depth of the circuit and thus determine the scale of the computation that can be carried out.

The noise can cause errors in quantum computations by causing qubits to lose their quantum state and become entangled with other qubits or the environment, a process known as decoherence. Hardware noise can introduce a bias that affects expectation values, even when working within these restrictions. Error-mitigation techniques have been developed to remove this bias and produce more accurate expectation values. However, these techniques come at a cost, such as repeating the computation with modified parameters, increased sampling costs, or additional classical postprocessing. Several schemes have been proposed and experimentally implemented to mitigate errors that occur during the application of the quantum circuit.

In this study, the author investigates the reduction of readout errors that arise during the final measurement phase of a computation. They specifically concentrate on calculating the expectation values of Pauli observables, which are a set of matrices that can represent any observable due to their Hermitian properties. Additionally, any observable that can be expressed as a polynomial combination of Pauli matrices, including local Hamiltonians, can be efficiently estimated by measuring the expectation values of Pauli observables due to the expectation value’s linearity.

Hermitian matrices

These are a special type of matrix that have the property that their transpose is equal to their complex conjugate. In quantum mechanics, observables are represented by Hermitian operators, which are matrices that satisfy this property. Pauli matrices are a set of three \(2\times 2\) Hermitian matrices that are commonly used in quantum mechanics to represent spin states and other physical quantities. Any observable can be expressed as a linear combination of these Pauli matrices, which means that they form a complete basis for the space of \(2\times2\) Hermitian matrices. Therefore, by measuring the expectation values of Pauli observables, we can estimate the expectation values of any observable in an efficient manner due to the linearity of the expectation value.

Measure a Pauli observable

After a quantum circuit has been applied, we can measure a Pauli observable. This is done by rotation of the observable to the computational basis using single-qubit Clifford gates, followed by measurement in this basis and some basic classical postprocessing. The process involves the following steps:

- Choose a Pauli observable to measure.

- Apply single-qubit Clifford gates to rotate the Pauli observable to the computational basis.

- Measure the qubits in the computational basis.

- Perform some basic classical postprocessing on the measurement results to obtain an estimate of the expectation value of the Pauli observable.

The single-qubit Clifford gates used in step 2 are a specific set of quantum gates that can be used to transform any Pauli observable into another Pauli observable or into the identity matrix. These gates are important because they allow us to perform measurements in a standard basis, which is easier to implement experimentally than measurements in other bases. After measuring the qubits in step 3, we obtain a string of 0s and 1s that corresponds to a particular computational basis state. By repeating this process many times and averaging over the results, we can estimate the probability distribution over all possible computational basis states. From this probability distribution, we can compute an estimate of the expectation value of the Pauli observable using some basic classical postprocessing techniques.

If there are no readout errors, the measurement output of \(n\) qubits can be represented by a probability distribution \(p\) over the \(2^n\) computational basis states. A classical noise map \(A\) is typically used to model readout errors, which maps the noise-free probability distribution \(p\) to a noisy distribution \(\tilde{p}=Ap\). The readout map \(A\) is a left-stochastic matrix with dimensions of \(2^n\times2^n\), where the element \(A_{i,j}\) represents the probability of measuring the \(i\)th computational basis state instead of the \(j\)th computational basis state, for \(i,j\in{0,1}^n\). For example, if \(n=2\), there are four possible computational basis states: \(|00\rangle\), \(|01\rangle\), \(|10\rangle\), and \(|11\rangle\). The element \(A_{00,01}\) denotes the probability of measuring \(|00\rangle\) but incorrectly reading it as \(|01\rangle\). Similarly, \(A_{10,11}\) represents the probability of measuring \(|10\rangle\) but incorrectly reading it as \(|11\rangle\).

Left-stochastic matrix

A left-stochastic matrix is a square matrix where each row sums to one and all its entries are non-negative. In other words, it is a matrix where the entries represent probabilities of transitioning from one state to another, and the sum of probabilities for each row is equal to one. In quantum computing, left-stochastic matrices can be used to model noise in quantum circuits, such as depolarizing noise or readout errors. An example of a left-stochastic matrix is:

\[\begin{pmatrix} 0.4 & 0.3 & 0.3 \\ 0.2 & 0.5 & 0.3 \\ 0.1 & 0.2 & 0.7 \\ \end{pmatrix}\]In this matrix, each row sums to one, and all entries are non-negative probabilities of transitioning from one state to another. For example, the entry in the first row and second column represents the probability of transitioning from state 1 to state 2, which is 0.3 in this case.

A common method to mitigate the impact of readout errors involves estimating the columns of the readout map \(A\) by measuring the output frequencies \(\hat{r}_x\) for different bit strings \(x\), and then applying the matrix \(A^{-1}\) for correction. To elaborate, we perform measurements on a quantum system and keep track of the frequency with which each computational basis state is observed. These frequency measurements enable us to estimate the columns of the readout map \(A\), which describe the likelihood of measuring each computational basis state correctly or incorrectly due to readout errors. Once we have obtained these column estimates, we can invert the matrix \(A\) using its inverse \(A^{-1}\) to correct for the errors.

The inverse of a matrix reverses its impact on vectors, so applying \(A^{-1}\) after measuring a vector corrects any errors introduced by \(A\). In this context, applying \(A^{-1}\) after measuring a quantum state corrects for any readout errors that may have occurred during the measurement process.

Example

Suppose we have a quantum system with two qubits, and we want to measure the expectation value of the Pauli observable \(Z_1 \cdot Z_2\) (i.e., the product of the \(Z\) Pauli matrices on qubits 1 and 2). To do this, we first prepare the system in some initial state (e.g., \(|00\rangle\)), then apply a quantum circuit that implements the desired operation (in this case, a CNOT gate followed by two Hadamard gates). After applying the circuit, we measure the system in the computational basis and record the frequency with which each computational basis state is observed. Suppose we obtain the following measurement results:

\(|00\rangle\): 1000 counts

\(|01\rangle\): 200 counts

\(|10\rangle\): 150 counts

\(|11\rangle\): 650 counts

Using these frequency measurements, we can estimate the columns of the readout map \(A\). For example, to estimate column 1 of \(A\) (which corresponds to measuring \(|00\rangle\)), we would divide the number of counts for \(|00\rangle\) by the total number of counts:

\(A_{1,1} = 1000 / (1000 + 200 + 150 + 650) = 0.571\)

Similarly, to estimate column 2 of \(A\) (which corresponds to measuring \(|01\rangle\)), we would divide the number of counts for \(|01\rangle\) by the total number of counts:

\(A_{2,1} = 200 / (1000 + 200 + 150 + 650) = 0.114\)

We can repeat this process for all four columns of \(A\) to obtain estimates for each entry.

Once we have estimated these columns, we can invert \(A\) using its inverse \(A^{-1}\) to correct for readout errors. In this case, since \(A\) is a left-stochastic matrix, its inverse is also left-stochastic, so we can simply apply \(A^{-1}\) to the measurement results to correct for errors. For example, suppose we measured the state \(|01\rangle\) but incorrectly read it as \(|00\rangle\). To correct for this error, we would apply the first column of \(A^{-1}\) (which corresponds to measuring \(|00\rangle\)) to the measurement result:

\[A^{-1} \cdot \begin{bmatrix}1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0\\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}0.571 \\ -0.114 \\ -0.086 \\ -0.371 \\ \end{bmatrix}\]The corrected measurement result is then given by the probabilities in the resulting vector, which sum to 1. In this case, we can see that the corrected probability of measuring \(|01\rangle\) is:

\(|01\rangle\): \(0.114 / (0.571 - 0.114 - 0.086 - 0.371) = 0.25\)

This corrected probability is higher than the original probability of measuring \(|01\rangle\), which was only \(200 / (1000 + 200 + 150 + 650) = 0.114\). By correcting for readout errors using \(A^{-1}\), we can obtain more accurate measurement results and improve the overall performance of our quantum system.

Explicitly representing and inverting the readout map \(A\) is only feasible for small system sizes or when the noise can be assumed to factorize, such that noise on individual or small groups of qubits can be modeled and inverted independently. The readout map \(A\) is a \(2^n \times 2^n\) matrix, where \(n\) is the number of qubits in the quantum system. As \(n\) increases, the size of \(A\) grows exponentially, making it increasingly difficult to represent and invert explicitly.

Example

If we have a system with just 10 qubits, then \(A\) will be a \(1024 \times 1024\) matrix. If we have a system with 20 qubits, then \(A\) will be a \(1,048,576 \times 1,048,576\) matrix. In general, the size of \(A\) grows as \(2^{2n}\), which quickly becomes infeasible to work with for large values of \(n\).

Furthermore, the readout map \(A\) is a tensor product of individual qubit readout maps, so noise is assumed to factorize. In other words, the probability of measuring a particular bit string in the computational basis depends only on the probabilities of measuring each qubit in that bit string independently. This means that if we can model and invert the noise on each qubit independently, then we can also model and invert the noise on the entire system.

Example

Suppose we have a system with two qubits, and we want to measure the expectation value of the Pauli observable \(Z_1 \cdot Z_2\). If we assume that noise on each qubit is independent and identically distributed, then we can model each qubit’s readout error using a single-qubit readout map \(A_i\) for \(i=1,2\). The overall readout map \(A\) for the two-qubit system is then given by \(A = A_1 \otimes A_2\), where \(\otimes\) denotes the tensor product. We can estimate columns of \(A\) by measuring output frequencies for different bit strings as described earlier and then apply its inverse to correct for readout errors.

However, if noise does not factorize in this way (e.g., if there are correlations between errors on different qubits), then modeling and inverting noise becomes much more difficult.

Experiments have revealed that noise tends to be correlated, making the use of product approximations to the stochastic matrix unreliable. A recent paper describes a readout-error-mitigation method that can handle correlated noise, with a formal guarantee of performance based on the strength of the noise. This method was both proposed and experimentally implemented in the paper. It avoids the need to explicitly invert the noise map, and the model can be represented concisely using \(O(poly(n))\) parameters.

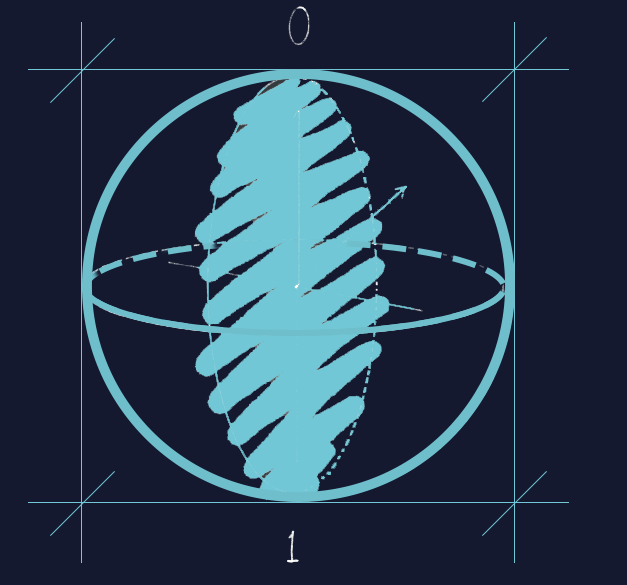

The twirled-readout method is a technique that adds uniform random Pauli bit flips prior to measurement to randomize the output channel. This randomness can help counteract biases caused by hardware imperfections by effectively “averaging out” these biases. The random bit flips are tracked and used in subsequent analysis to correct for these biases and obtain more accurate measurements. The Pauli bit flips transform the effect of any arbitrary noise map into a single multiplicative factor per Pauli observable, which diagonalizes the measurement channel and simplifies bias correction.

The method can be applied to a wide range of quantum systems beyond single-qubit models, and it requires no prior assumptions or models of the readout-error process other than the ability to initialize the circuit in the zero state. The shot-noise variance of the mitigated estimate is inversely proportional to the magnitude of the noise factor, and the necessary number of measurement samples for a desired estimation accuracy can be analyzed based on the underlying noise strength.

Method

Consider a system composed of \(n\) qubits and a collection of Pauli operators denoted by \(\mathcal{P}\). Each \(P_q\) corresponds to a unique Pauli operator indexed by \(q\) in the range \([0, 4^n-1]\). There are four types of Pauli matrices (\(I\), \(X\), \(Y\), and \(Z\)) that can be applied to each qubit, and the system contains \(n\) qubits. The indices for the Pauli-Z operators are given by \(\mathcal{Z} := [0, 2^n-1]\), and the set of indices for the Pauli-X operators is represented by \(\chi\). For \(r\) and \(s\) belonging to the set \(\mathbb{Z}_2^n\), the inner product is defined as

\[\langle r, s\rangle = \sum_i r_s\]Here, \(Z^s\) is defined as \(\bigotimes_{i=1}^n\sigma_z^{S_i}\) and \(X_s\) is defined similarly, with \(\sigma_z\) replaced by \(\sigma_x\). Define \(P_z\) as \(Z^s\) interpreted as an integer index.

In this system, we use binary vectors \(r\) and \(s\) of length \(n\), where each element is either 0 or 1. To calculate the inner product \(\langle r,s\rangle\), we add up the product of corresponding elements in \(r\) and \(s\). To represent an operator, use the notation \(Z^s\) which is obtained by taking the tensor product (symbolized by \(\otimes\)) of \(n\) Pauli-Z matrices, with each matrix acting on a different qubit in the system. For each qubit \(i\) from 1 to \(n\), include \(\sigma_z\) in the tensor product if \(s_i=0\), and we include \(-\sigma_z\) if \(s_i=1\).

Given the initial state

\[\rho_0=(|0\rangle\langle 0|)^{\otimes n}=\frac{1}{2^n}(I+\sigma_z)^{\otimes n}=\frac{1}{2^n}\sum_{j\in Z}P_j\]we aim to approximate the Pauli-Z component \(P_i\) in the state

\[\rho=U\rho_0U^\dagger\]where \(U\) is an operator. Specifically, we want to evaluate

\[\langle P_i\rangle_\rho=\text{Tr}(P_i\rho)\]Initial state

The state $|0\rangle$ represents the ground state of a single qubit, which is defined as the eigenstate of the Pauli-Z operator $\sigma_z$ with eigenvalue $+1$. Similarly, the state $|1\rangle$ represents the excited state of a single qubit, which is defined as the eigenstate of $\sigma_z$ with eigenvalue $-1$.

The projection operator onto the ground state $|0\rangle$ is given by:

\begin{equation} |0\rangle\langle 0| \end{equation}

Therefore, $|0\rangle\langle 0|^{\otimes n}$ is a projection operator that projects onto the tensor product of $n$ ground states. This operator projects any quantum state onto the subspace spanned by $|0\rangle$. We can express this projection operator in terms of Pauli matrices as follows:

\[\begin{align} |0\rangle\langle 0| &= \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix} \\ &= \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 \end{pmatrix} \\ &= \frac{1}{2}\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} + \frac{1}{2}\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{pmatrix} \\ &= \frac{1}{2}(I + \sigma_z) \end{align}\]Here, we have used the fact that $\sigma_z |0\rangle = |0\rangle$ and $\sigma_z |1\rangle = -|1\rangle$, so that $\sigma_z = |0\rangle\langle 0| - |1\rangle\langle 1|$. We have also used the fact >that $I = |0\rangle\langle 0| + |1\rangle\langle 1|$.

Therefore, we can write the initial state as:

\begin{equation} \rho_0 = (|0\rangle\langle 0|)^{\otimes n} = \left(\frac{1}{2}(I + \sigma_z)\right)^{\otimes n} \end{equation}

The expression $(I + \sigma_z)^{\otimes n}$ represents the tensor product of $n$ copies of the operator $(I + \sigma_z)$, where $I$ is the identity matrix and $\sigma_z$ is the Pauli-Z operator.

Using the binomial theorem, we can expand this expression as follows:

\[\begin{align} (I + \sigma_z)^{\otimes n} &= (I + \sigma_z) \otimes (I + \sigma_z) \otimes ... \otimes (I + \sigma_z) \\ &= I^{\otimes n-1} \otimes (I + \sigma_z) + I^{\otimes n-2} \otimes (I + \sigma_z) \otimes I + ... \\ &\qquad ...+ (I + \sigma_z) \otimes I^{\otimes n-2} \otimes ... \otimes I^{\otimes 0} \end{align}\]We can use the distributive property of tensor products. Specifically, we can write:

\[\begin{align} (I + \sigma_z) \otimes (I + \sigma_z) &= I\otimes I + I\otimes\sigma_z + \sigma_z\otimes I + \sigma_z\otimes\sigma_z \\ &= I^{\otimes 2} + (\sigma_z)^{\otimes 1} I^{\otimes 1}+ I^{\otimes 1} (\sigma_{z})^{\otimes 1}+ (\sigma_{z})^{\otimes 2} \end{align}\]Here, we have used the fact that $\sigma_{z}\,\cdot\,\sigma_{z}=I$, which follows from the definition of the Pauli-Z operator.

We can now use this result to expand $(I+\sigma_{z})^{\otimes n}$ as follows:

\(\begin{align} (I+\sigma_{z})^{\otimes n}&=(I+\sigma_{z})^{\otimes n-1}(I+\sigma_{z})\\ &=[(I+\sigma_{z})^{\otimes n-2}(I+\sigma_{z})]\,(I+\sigma_{z})\\ &=\cdots\\ &=[(I+\,\underbrace{\cdots}_{n-2}\,+~\underbrace{(I+\,\underbrace{\cdots}_{n-3}\,+~\cdots~+\,(I+\sigma_{z}))}_{n-1\text{ terms}}]\,(I+\sigma_{z})\\ &=I^{\otimes n-1}\otimes(I+\sigma_{z})+I^{\otimes n-2}\otimes(I+\sigma_{z})\otimes I + \cdots \\ & \cdots + (I+\sigma_{z})\otimes I^{\otimes n-2} \otimes \cdots \otimes I^{\otimes 0} \end{align}\) This gives us the desired expansion of $(I+\sigma_{z})^{\otimes n}$ as a sum of tensor products of $I$ and $\sigma_z$.

Here, we have used the distributive property of tensor products to expand out each term in the product.

Now, notice that each term in this expansion has exactly $j$ factors of $\sigma_z$, where $j$ ranges from $0$ to $n$. We can group together all terms with $j$ factors of $\sigma_z$, and use the fact that $(\sigma_z)^2 = I$ to simplify:

\[\begin{align} (I + \sigma_z)^{\otimes n} &= I^{\otimes n} + {n\choose 1}\,\sigma_z^{1}\, I^{\otimes n-1}+ {n\choose 2}\,\sigma_{z}^{2}\, I^{\otimes n-2}+\cdots \\ & \cdots + {n\choose n-1}\,\sigma_{z}^{n-1}\, I^{\otimes 1}+ \sigma_{z}^{n}\\ &= \sum_{j=0}^n {n\choose j}\, \sigma_z^{j}\, I^{\otimes n-j} \end{align}\]This gives us the desired expression $(I + \sigma_z)^{\otimes n} = \sum_{j=0}^n {n\choose j}\, \sigma_z^{j}\, I^{\otimes n-j}$, which we can use to simplify our definition of $\rho_0$.

Since $I^{n-j}$ is just the identity matrix acting on $n-j$ qubits, we can simplify this expression further:

\begin{equation} (I + \sigma_z)^{\otimes n} = \sum_{j=0}^n {n \choose j} \sigma_z^j \end{equation} Now we can substitute this expression back into our definition of $\rho_0$:

\begin{equation} \rho_0 = \frac{1}{2^n}(I + \sigma_z)^{\otimes n} = \frac{1}{2^n}\sum_{j \in Z} P_j \end{equation}

Trace

Let’s consider a general operator $A$ acting on an $n$-dimensional Hilbert space. We can write $A$ as a matrix in some basis, where the rows and columns of the matrix correspond to the basis states. For example, if we choose the computational basis ${|0\rangle, |1\rangle, \ldots, |n-1\rangle}$, then we can write:

\[A = \begin{pmatrix} A_{00} & A_{01} & \cdots & A_{0,n-1} \\ A_{10} & A_{11} & \cdots & A_{1,n-1} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ A_{n-1,0} & A_{n-1,1} & \cdots & A_{n-1,n-1}\end{pmatrix}\]Here, $A_{ij}$ denotes the $(i,j)$th element of the matrix. The trace of $A$ is then given by:

\[\mathrm{Tr}(A) = \sum_i A_{ii}\]In other words, we sum up all diagonal elements of the matrix.

Note that the trace is independent of the choice of basis. If we choose a different basis ${|a\rangle}$ with corresponding dual basis $\langle a|$, then we can write:

\[A = \sum_{a,b} |a\rangle\langle b| \langle b | A | a\rangle\]Using this expression and the fact that $\langle a | b\rangle = \delta_{ab}$ for an orthonormal basis, it is straightforward to show that:

\[\mathrm{Tr}(A) = \sum_a \langle a | A | a\rangle\]This expression shows that the trace is simply the sum of diagonal elements in any basis.

Assuming the initial state is $\rho_0$, and all measurements are performed in the computational basis, we can evaluate $\langle P_i\rangle_\rho=\operatorname{Tr}(P_i\rho)$ only for $P_i\in$ Pauli-Z. The Pauli-Z operator has non-zero expectation values only for states that have definite values of Z (either +1 or -1). Therefore, when measuring a qubit in state $|\psi\rangle$ in the computational basis and getting outcome 0, we know that $|\psi\rangle$ must be an equal superposition of $|0\rangle$ and $|1\rangle$, which implies that it does not have a definite value of Z. Thus, measuring $P_i$ on such a state will result in an outcome of 0 with a probability of 1/2, regardless of the actual value of $|\psi\rangle$.

As a result, to evaluate $\langle P_i\rangle_\rho=\operatorname{Tr}(P_i\rho)$, we need to consider only the states that have definite values of Z, which belong to the Pauli-Z group (also called the eigenstates of $P_i$). This group consists of all possible tensor products of Pauli-Z matrices on each qubit. Hence, when we say “only $P_i\in$ Pauli-Z,” we mean that we can compute the expectation value of $P_i$ for any state that belongs to the Pauli-Z group, but not for any other states.

We can obtain the expectation values for other Pauli operators by incorporating an appropriate basis change in the operator $U$. To estimate $\langle P_i\rangle_\rho=\operatorname{Tr}(P_i\rho)$, we run various instances of the given circuit.

The circuit is characterized by the Pauli index $q$ and unitary $C$ (or the circuit that realizes it). If we select $C$ to be the identity, the circuit simplifies.

The index set $S$ will determine the sampling of the Pauli index $q$. Its specific definition will be provided at a later point in this paper. Paper describes the procedure to obtain the measurement outcomes for $N$ circuit instances using the protocol presented in this work.

Protocol 1. AcquireData($\mathcal{S}$,C,N)

1

2

3

4

5

6

Initialize an empty data set D

for i = 1,...,N do

Uniformly sample q from index set S

Execute the circuit with Pauli P_q and unitary C

Record the measurement outcome x and add tuple (q,x) to D

return D

The acquired data corresponds to measurement outcomes that can be expressed as elements $x \in Z_2^n$. Upon obtaining this data, a classical postprocessing step is performed using a function that will be further detailed.

\[f(\mathcal{D},s)=\frac{1}{|\mathcal{D}|}\sum_{(q,x)\in D}\gamma_{s,q}(-1)^{\langle s, x \rangle}\]The value of $\gamma_{a,b}$ is determined as follows: if the Pauli operators $P_a$ and $P_b$ commute, then $\gamma_{a,b}$ equals 1. If they do not commute, then $\gamma_{a,b}$ equals -1. However, if we flip the measurement bits according to the sampled $q$ value, the sign changes can be omitted.

Classiscal postprocessing of the acquired data

The expression $f(\mathcal{D},s)=\frac{1}{|\mathcal{D}|}\sum_{(q,x)\in D}\gamma_{s,q}(-1)^{\langle s, x \rangle}$ used to estimate the expectation value of a certain observable on a quantum state.

Here, $D$ is a set of pairs $(q,x)$, where $q$ is an $n$-tuple of integers from ${0,1,2,3}$ (i.e., a Pauli index) and $x$ is an $n$-tuple of binary values (i.e., either 0 or 1). The parameter $s$ is also an $n$-tuple of binary values. The notation $\langle s,x\rangle$ denotes the inner product of the two vectors modulo 2 (i.e., the sum of their element-wise product modulo 2).

The function $\gamma_{s,q}$ is defined as follows:

\[\gamma_{s,q} = \begin{cases} +1 & \text{if } \langle s,q\rangle = 0 \\ -1 & \text{if } \langle s,q\rangle = 1 \end{cases}\]In other words, $\gamma_{s,q}$ depends on the inner product between $s$ and $q$, and takes on values $\pm 1$ depending on whether this inner product is even or odd.

The expression $(-1)^{\langle s,x\rangle}$ in the summand corresponds to a phase factor that depends on both $s$ and $x$. This phase factor changes sign whenever the inner product $\langle s,x\rangle$ changes from even to odd or vice versa.

The function $f(D,s)$ computes an average over all pairs $(q,x)\in D$ of the product $\gamma_{s,q}(-1)^{\langle s,x\rangle}$. This average is normalized by the size of $D$, which is denoted by $|D|$. The resulting value is an estimate of the expectation value of a certain observable on a quantum state, where the observable is defined in terms of Pauli operators and depends on the choice of $s$.

The specific choice of $D$ and $s$ depends on the problem being solved. In general, we want to choose $D$ and $s$ in such a way that the resulting estimate has low variance and is unbiased. One common choice is to take $D$ to be a set of $N$ pairs $(q,x)$ that are randomly sampled from some distribution, and to choose $s$ to be a random $n$-tuple of binary values. The distribution from which we sample the pairs $(q,x)$ depends on the specific problem being solved, but is often chosen to be uniform or close to uniform.

The function $f(\mathcal{D},s)$ can be efficiently computed using a quantum circuit that prepares the state $\frac{1}{\sqrt{|\mathcal{D}|}}\sum_{(q,x)\in \mathcal{D}}(-1)^{\langle s,x\rangle}|q\rangle|x\rangle$, where $|q\rangle$ and $|x\rangle$ denote the computational basis states corresponding to the Pauli index $q$ and binary tuple $x$, respectively. This state can be prepared using a combination of Hadamard gates, controlled-$Z$ gates, and single-qubit rotations.

Once we have prepared this state, we can measure the expectation value of an observable by applying a sequence of Pauli operators (corresponding to the observable) to each qubit in turn, and measuring each qubit in the computational basis. The resulting bit string gives us an estimate of the expectation value, which can be used to compute various quantities of interest (e.g., gradients for optimization).

The protocol for estimating <$Z^s \rho$> is then as in this protocol

Prortocol 2

1

2

3

D_0=AcquireData(Chi,I,N)

D_1=AcquireData(Chi,U,N)

Return estimate f(D_1,s)/f(D_0,s)

It is worth noting that the data obtained during steps 1 and 2 of Protocol 2 can be repurposed to evaluate the quantity in step 3 for different values of $s$. Additionally, the data acquired in step 1 is independent of $U$ and can therefore also be used. For convenience, we set the number of samples to $N$ for each of the two data sets. However, it is possible to use different sample sizes for each of these steps, as required.

Derivation

Analysis

Simulation

Conclusion

References

- van den Berg, E., Minev, Z. K. & Temme, K. Model-free readout-error mitigation for quantum expectation values. Physical Review A 105, (2022).

- Chen, Y., Farahzad, M., Yoo, S. & Wei, T.-C. Detector Tomography on IBM Quantum Computers and mitigation of an imperfect measurement. Physical Review A 100, (2019).

- Bravyi, S., Sheldon, S., Kandala, A., Mckay, D. C. & Gambetta, J. M. Mitigating measurement errors in multiqubit experiments. Physical Review A 103, (2021).

Leave a comment