Engineering Efficient Atom Traps: A Focus on Strontium and Relevant Techniques

Laser Cooling and Trapping

Laser cooling and trapping are fascinating phenomena that have been comprehensively explored in scholarly textbooks and review articles. This portion of our discussion delves into the distinguishing attributes of laser cooling, shining a light on a key technique known as Doppler cooling.

The Doppler cooling technique is best understood as a process involving an atom moving with a velocity $v$ within a light field. This field is created by counter-propagating laser beams that are characterized by an intensity $I$, wavevectors $\pm k$, and a detuning $\Delta$, separated from the atom’s bare transition frequency, denoted as $\omega_0$.

A fundamental aspect to consider in this context is the velocity-dependent radiation pressure force. This force is represented by the equation

\[\begin{aligned} F(v, \Delta) &= F_k(v) - F_{-k}(v) = \hbar k \Gamma_{sc}(\Delta - kv) - \hbar k \Gamma_{sc}(\Delta + kv) \\ &= \hbar k \Gamma_{sc} \frac{s_0}{2} \left(\frac{1}{1 + s_0 + 4 \frac{(\Delta - kv)^2}{\Gamma^2}} + \frac{1}{1+s_0+4\frac{(\Delta+kv)^2}{\Gamma^2}}\right) \end{aligned}\]Within this equation, $s_0 = I/I_{sat}$ stands as the saturation parameter, a quantity that describes the intensity in relation to the saturation intensity $I_{sat} \propto \omega^3_0 \Gamma$. The latter is proportional to $\Gamma$, signifying the linewidth of the atomic transition.

Red detuning introduces a linear damping force essential for cooling, the final temperature of which is constrained by the Doppler temperature.

\[T_{Doppler} \approx \frac{\hbar \Gamma}{2 k_B}\]This process entails a delicate balance between the bandwidth of captured velocities and the minimum temperature attainable. Investigations have been conducted regarding its application to sodium.

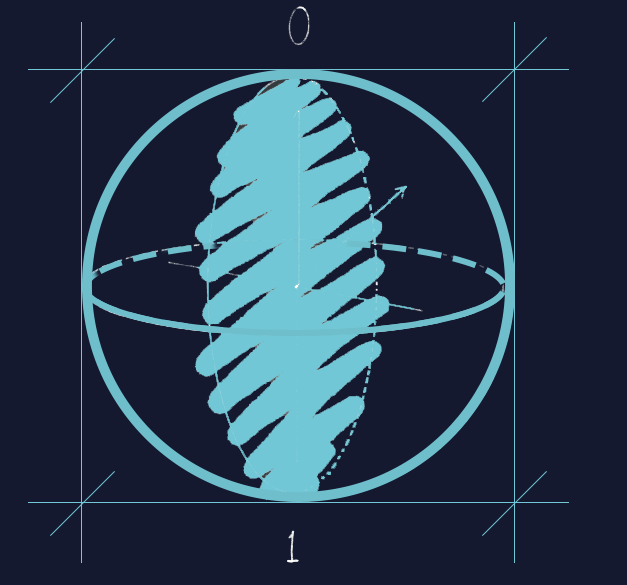

Deciphering the Magneto-Optical Trap (MOT)

The Magneto-Optical Trap (MOT) serves to confine atoms within a specific velocity range and spatial volume. It accomplishes this by incorporating a three-dimensional magnetic field gradient to scatter spatially dependent photons from select beams.

The trap’s capture volume is largely determined by the linewidth rate $\Gamma$ in relation to a particular magnetic field gradient. This relationship provides a pathway to larger trap sizes facilitated by higher trapping forces. The force is finally described by

\[F(v,x) = \beta(\Gamma)v - \beta(\Gamma)\kappa(g_j m_j)\frac{\delta B}{\delta x}x\]To augment the number of atoms in MOTs, experts employ pre-cooling and pre-collimating methods. These include techniques such as the Zeeman slower and 2D-MOT.

The Zeeman slower utilizes a magnetic field gradient to decrease the speed of atoms, keeping them resonant, while the 2D-MOT generates a collimated atom beam that exhibits coldness in two dimensions and is spatially confined. This makes it optimal for low-pressure areas.

Dipole Traps and their Application

Dipole traps utilize far-detuned light to confine atoms within a conservative potential shaped by the laser beam profile. This concept can be comprehended via a semi-classical oscillator model or through exploring the effects of intensity-dependent light shifts.

The trap potential for atoms is determined by the intensity profile of the laser beam, while the ideal dipole trap is achieved by opting for a large detuning to decrease the scattering rate more rapidly than the potential depth.

Assessing the impact of a far-detuned laser field on a dipole trap requires consideration of multiple transitions and dipole matrix elements. The detuned light field triggers a mix of states, leading to a light shift that creates a conservative potential for the atoms trapped within.

Reference

- Baumgartner, A. A new apparatus for trapping and manipulating single Strontium atoms. (2017).

Leave a comment