Brief Reviews on Variational Quantum Algorithms

This review is written by non-expert and used for personal study only. This post content is continuously improving.

The intrinsic versatility of VQAs offers a robust framework for tackling diverse problems using quantum computers. The essence of VQAs rests on three pivotal elements: defining a cost function, proposing an ansatz, and training the parameters within a hybrid quantum-classical feedback loop. VQAs leverage the computational prowess of quantum computers to estimate the cost function while tapping into classical optimizers to train the parameters.

The Key Components of Variational Quantum Algorithms

To function efficiently, a VQA requires a cost function, which maps trainable parameters to real numbers with the primary objective of identifying the global minima. An ideal cost function should be efficiently estimable, operationally meaningful, and trainable while remaining faithful to the computation at hand. For NISQ hardware, the importance of efficient cost-evaluation circuits cannot be overstated, given the limited qubit counts and brief decoherence times.

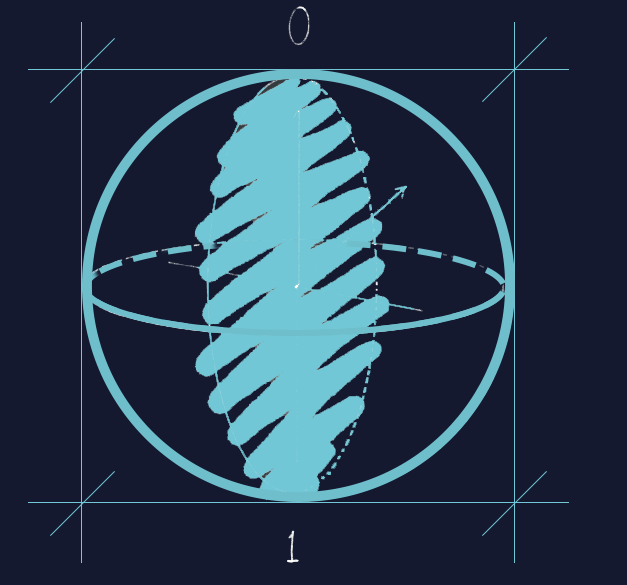

The ansatz, another essential component of VQAs, serves to dictate the parameter form and minimize the cost. Ansatz structures can be either problem-inspired or problem-agnostic, and parameters can be encoded in a unitary $U(\theta)$ that is applied to input states. Ansatzes can be manifested as a sequence of unitaries applied one after the other.

The hardware-efficient ansatz presents a viable method to lessen the circuit depth required to implement $U(\theta)$ on specific quantum hardware by utilizing a set of quantum gates unique to the hardware’s connectivity and interactions. Despite the potential trainability issues of “layered” hardware-efficient ansatzes when randomly initialized, this ansatz remains a versatile and beneficial tool for examining Hamiltonians that mirror the device’s interactions.

The Unitary Coupled Clustered (UCC) ansatz is another popular method extensively utilized in quantum chemistry to determine the ground-state energy of a fermionic molecular Hamiltonian. This ansatz is applied in a quantum computer by mapping fermionic operators to spin operators via Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformations, culminating in an ansatz of the form

\[U(\theta) = U_L(\theta _L) \cdots U_2(\theta _2)U_1(\theta _1)\]In addition, the Quantum Alternating Operator Ansatz has found application in the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) to seek approximate solutions for combinatorial optimization problems. This ansatz comprises a sequence of problem unitaries and mixer unitaries that map an input state to the ground state of a specified problem Hamiltonian and is computationally universal for certain Hamiltonians.

The variational Hamiltonian ansatz, on the other hand, prepares a trial ground state for a given Hamiltonian by Trotterizing an adiabatic state preparation process and has been employed for quantum chemistry, optimization, and quantum simulation problems. The optimization of quantum circuit structures can reveal refinements missed by merely optimizing continuous parameters. This challenge can be conceptualized as a sparse model problem where heuristic approximations have shown promise.

Machine learning tools have emerged as effective instruments for developing variational ansatzes for a range of VQA applications. Exploring different ansatz variants simultaneously has demonstrated remarkable performance. Inclusion of device-level parameters in the ansatz definition adds an extra layer of flexibility and establishes a link to quantum optimal control. This relationship can aid in deciphering the translation from logical to physical device parameters and mitigating the impacts of coherent noise.

Hybrid ansatzes offer a unique approach by integrating classical strategies with quantum ansatzes to simplify quantum operations. These ansatzes utilize trainable linear combinations of parameterized states and tensor network techniques. Another hybrid approach combines variational Monte Carlo techniques with a quantum ansatz to apply the ‘Jastrow operator’ to a parameterized quantum state, leading to more accurate results.

Numerous ansatzes have been formulated to construct mixed states for systems at finite temperature. One method involves preparing a pure state that has the reduced state as a subsystem, albeit at the expense of up to $2n$ qubits. Alternatively, a probability distribution and a set of states can be trained to construct the mixed state as a statistical ensemble.

The expressibility and entangling capability of ansatzes play a crucial role in their effectiveness in preparing target states. Gradients prove vital for optimizing VQAs, and the parameter-shift rule allows for the analytical evaluation of the gradient. Higher-order derivatives can also be evaluated using this rule, while other types of derivatives, such as the metric tensor, can be used in optimization algorithms.

Applications of Variational Quantum Algorithms

VQAs allow for task-oriented programming and can tackle a broad spectrum of tasks, making them suitable for virtually all envisioned applications for quantum computers. The most renowned application of VQAs is the estimation of low-lying eigenstates and corresponding eigenvalues of a given Hamiltonian, which can be achieved through the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) algorithm. VQE is designed to find the ground-state energy of a Hamiltonian and can be used to identify excited states of H through a multitude of methods.

VQAs can also simulate the dynamical evolution of a quantum system using a shallow depth circuit to lessen the influence of hardware noise. Iterative variational algorithms consider trial states and map the state’s evolution to the evolution of the parameters. The subspace approach uses the weighted subspace VQE to simulate dynamics in the subspace of the low-energy eigenstates.

VQAs are also capable of solving classical optimization problems, with QAOA being a prominent VQA for quantum-enhanced optimization. QAOA encodes the classical objective function in a quantum Hamiltonian and uses variational parameters to optimize the evolution time intervals.

VQAs for Mathematical Problems and Quantum Error Correction

Beyond optimization, VQAs have been proposed to tackle mathematical problems like linear systems of equations and integer factorization. The objective of VQAs is to achieve heuristic scalings comparable to non-near-term algorithms while maintaining the algorithm requirements compatible with the NISQ era. VQAs have demonstrated potential for exponential speed-up for the quantum linear systems problem (QLSP) and factoring.

Quantum error correction (QEC) serves to safeguard qubits from hardware noise, but its implementation is beyond the capabilities of NISQ devices. Two VQAs have been introduced to resolve this issue by discovering or compiling error mitigation circuits to suppress dominant error channels and to achieve fault tolerance by using smaller codes. These VQAs are variational quantum unsampling (VQU) and variational quantum decoders (VQD), respectively.

VQAs in Quantum Machine Learning

Quantum machine learning (QML) is another exciting field where VQAs are showing considerable promise. VQAs can be used in unsupervised learning tasks such as clustering, manifold learning, and dimensionality reduction. This approach requires a measure of similarity (a kernel) between data points. In quantum computers, this measure is given by the transition amplitude or the fidelity, which can be estimated with VQAs.

Similarly, supervised learning tasks, which require a model to be trained on labeled data, can benefit from VQAs. For example, quantum support vector machines use VQAs to estimate the kernel, while quantum neural networks can use VQAs to train the model parameters.

The Challenges and Prospects of VQAs

While VQAs are demonstrating considerable potential, there are challenges to overcome. These include the notorious barren plateau problem, which indicates that for certain choices of random initialization and cost functions, the gradient of the cost function has exponentially vanishing variance, making optimization difficult. Also, VQAs can be sensitive to noise due to the intermediate measurements and long coherence times they require.

Moreover, the problem of verifying and validating the results of VQAs on NISQ devices persists, as classical computation can often outperform quantum ones in this era, meaning we can check the results. When quantum advantage is achieved, this becomes a challenge.

Nonetheless, future prospects for VQAs are bright. By drawing from fields such as control theory, machine learning, and tensor network theory, we can refine VQAs and their training strategies, and more efficiently explore their parameter landscape. Furthermore, as quantum hardware advances, the capacity for VQAs to solve practical problems will increase, pushing us closer to achieving quantum advantage.

Reference

- Cerezo, M. et al. Variational quantum algorithms. Nature Reviews Physics 3, 625–644 (2021).

Leave a comment