Brief Reviews on Quantum Computational Chemistry

This review is written by non-expert and used for personal study only. This post content is continuously improving.

Recent advancements in quantum hardware have sparked optimism, offering potential solutions for problems in chemistry, physics, and materials science previously deemed insoluble by classical methods. As technology and theory continue to evolve, the prospect of quantum simulations achieving higher accuracy than traditional experimental methods looms on the horizon.

Quantum algorithms have shown great promise for decoding intricate chemistry problems. However, these experiments are limited to smaller systems, hampered by the existing constraints of quantum hardware. The crux of revolutionary chemistry simulations, quantum error correction, demands more qubits and decreased error rates, which are currently out of reach.

Quantum computational chemistry devotes its attention to unveiling the ground energy levels of chemical systems—a cornerstone of classical computational chemistry—while extending its utility to additional problem domains. This article probes the confluence of quantum computing and classical computational chemistry, mapping chemistry problems onto quantum computers, and uncovering the ground and excited states of chemical systems.

This review paper concludes by comparing classical techniques and quantum approaches, estimating resources for various quantum methodologies. This comparison helps researchers unravel the immense potential nestled within the field of quantum computational chemistry. While several studies focus on quantum computational chemistry, the spotlight here is on practical strategies to solve the electronic structure problem using variational algorithms and the quantum phase estimation algorithm.

Quantum Computing and Simiulation

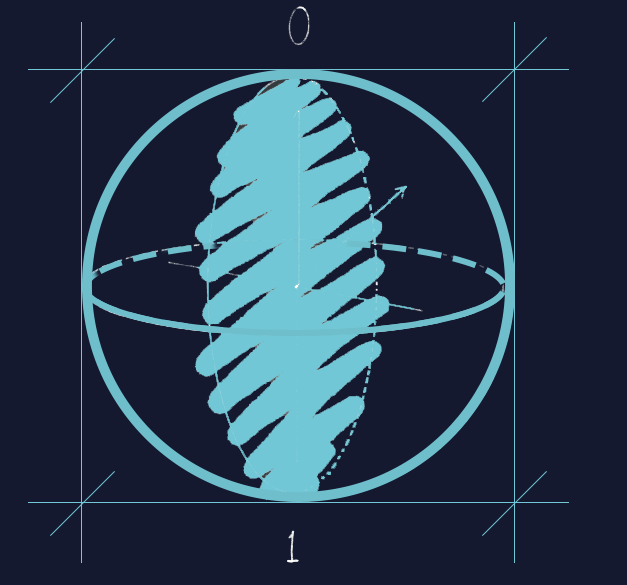

This review concentrates on the qubit-based circuit model of quantum computing. It manipulates the fundamental unit of information—the qubit—using quantum gates. These gates operate on basis state vectors concurrently, offering a level of parallelism constrained only by measurement. On measuring in the computational basis, the qubit state settles into either state $\vert0\rangle$ or state $\vert1\rangle$, eschewing a superposition.

A quantum system with n qubits is described by a vector in the $2^n$-dimensional Hilbert space, formed by the tensor product of the individual qubit’s Hilbert spaces. Quantum states can be classified as either “product” or “entangled”. Quantum circuits, composed of single- and two-qubit gates acting on qubits, can be illustrated mathematically by a sequence of gates operating on an initial state.

\[\vert \varphi\rangle = \prod_k U_k^{i_k, j_k}(\overrightarrow{\theta}_k)\vert\bar{0}\rangle\]Logical qubits are encoded into physical qubits to shield against decoherence, though error-checking procedures can inadvertently generate additional errors. Constructing circuits in a fault-tolerant manner can minimize error propagation, enabling computations to scale arbitrarily. The surface code, a widely researched error-correction code, is suitable for 2D qubit grids with nearest-neighbor connectivity.

Feynman’s proposition that near-term quantum computers could be harnessed for quantum system simulations is closer than ever to realization. This review spotlights digital quantum simulation of many-body quantum systems, casting the problem onto a set of gates implementable by a quantum computer.

Chemistry problems that can be simulated on a quantum computer can be categorized into static and dynamic problems, with the latter involving the evolution of wave functions over time. Techniques for solving dynamic problems, such as using a Trotter circuit or variational methods to evolve a Hamiltonian, are efficient for local Hamiltonians and fall within the BQP complexity class.

Quantum dynamics simulations can glean valuable data from time-evolved systems, such as electronic charge density distribution or particle correlation functions. The process of mapping chemical problems onto a quantum computer requires a precise depiction of both nuclear and electron spin orbital dynamics, where grid-based methods prove the most dependable. Furthermore, static properties can be acquired by mapping target wave functions onto qubit wave functions and utilizing quantum computers to compute the expectation value of desired observables, such as energy eigenstates.

Classical Computational Chemistry

Through the utilization of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, researchers pinpoint the electronic structure of molecules. By solely resolving the electronic Hamiltonian, they strive to identify energy eigenstates and eigenvalues. The quest extends to outlining potential energy surfaces of the molecule across varying nuclear configurations. This meticulous energy measurement plays a pivotal role in determining the rates of chemical reactions. Precision is paramount, with ‘chemical accuracy’ delineated as an error threshold less than $1.6 × 10^{−3}$ hartree in energy values at all points on the potential energy surface.

As the labyrinth of computational chemistry expands, quantum computers rise to the forefront as potential tools to navigate the intricacies of strongly correlated systems. These systems, characterized by wave functions with extensive entanglement, encompass catalysts and high-temperature superconductors.

Transition metals, frequently harnessed as catalysts, exhibit strong correlation, complicating in silico studies. Furthermore, enzymes like Nitrogenase, integral for nitrogen fixation, contain critical transition metal compounds. High-temperature superconductors are another class of strongly correlated systems demanding sophisticated models for comprehensive understanding. Quantum computing promises resources that can overcome these prevailing limitations in system studies.

The principles of quantum mechanics, particularly the Pauli Exclusion Principle, dictate the behavior of electronic wave functions. This principle mandates antisymmetry under the exchange of any two electrons. Two quantization techniques — first and second quantization — ensure this requisite antisymmetry.

Choosing between these techniques isn’t influenced by the decision to use a basis set or grid-based method. Basis sets ensure the energy converges accurately from above as the number of basis functions approaches infinity. Grid-based methods, however, do not display this property.

First Quantization

First quantized simulation methods enable simulation on classical computers via a discretized spatial grid. However, the memory requirement scales exponentially with electron numbers, rendering it infeasible for larger systems. In contrast, grid-based methods are particularly advantageous for chemical reaction dynamics and situations where the Born-Oppenheimer approximation falls short, as they provide an equal footing to both nuclei and electrons.

Leading studies have emphasized the potential of grid-based methods to incorporate the motion of nuclei in electronic structure calculations. Basis set methods leverage M basis wave functions to simplify electron spin orbitals, consequently reducing the resources needed to simulate chemical systems.

The many-electron wave function is crafted as a Slater determinant, a product of antisymmetrized single-electron basis functions. Even though first quantized basis set methods are seldom utilized in classical computational chemistry, they have been repurposed effectively in quantum computational chemistry. The second quantized basis set approach is a natural progression from its first quantized counterpart.

Second Quantization

Second quantized grid-based methods have been delved into by researchers and are a logical extension of the discourse on second quantized basis sets. These methods utilize a real space grid with basis functions that are delta functions located at grid points.

On the other hand, classical computation methods, such as Hartree-Fock (HF), multiconfigurational self-consistent field (MCSCF), configuration interaction (CI), and coupled-cluster (CC) methods, present viable options for approximating the ground state wave function with a confined number of Slater determinants. These methods generate parametrized trial states that progressively approach the ground state.

Each classical computation method carries its own strengths and limitations. The HF method offers a mean-field technique optimizing the spatial form of spin orbitals to find the dominant Slater determinant. However, its negligence towards dynamic and static correlation effects can result in subpar ground state wave function approximations.

The MCSCF method compensates for static correlation with several Slater determinants, delivering an approximation closer to the exact wave function. However, the inclusion of dynamic correlation energy requires supplementary techniques like multireference configuration interaction and multireference coupled cluster.

The CI method performs exceptionally at recovering dynamic correlation but falls short in recouping static correlation. It also suffers from a slow convergence rate to the full configuration interaction wave function and lacks size-extensiveness and consistency.

Lastly, the CC method facilitates correlation energy recovery using a product parametrization. It usually truncates at lower excitation levels due to high computational costs, yet it offers faster convergence than the CI method.

The field of computational chemistry is not static but is continually evolving. Conventional orbital basis sets are commonly utilized in classical computational chemistry to approximate the system’s “true” orbitals. However, these may not be optimal for quantum computing due to the large number of resulting Hamiltonian terms.

Quantum computing has seen the introduction of plane wave and plane wave dual basis sets, which diagonalize kinetic and potential operators, reducing Hamiltonian terms and potentially hastening quantum chemistry algorithms. Meanwhile, Gausslet and discontinuous Galerkin sets may need fewer functions for accurate molecule description.

Quantum Computational Chemistry Mappings

Primarily, quantum simulations can be conducted utilizing a discrete single-particle basis or through grid-based methodologies. Grid-based approaches pave the way for representing the wave function of an N-particle system on a discretized grid, featuring P points per axis.

Storing the complex amplitudes needed for large quantum systems becomes feasible with the aid of quantum computers. Intriguingly, grid-based techniques circumvent the need for the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, thereby ensuring the equal treatment of electrons and nuclei.

The number of qubits required to store the wave function in these methods is calculated by the formula $(3m+1)N$, with m representing an arbitrary number that determines the precision of the simulation.

While grid-based techniques have been efficiently tailored for quantum simulation, their applications extend to resolving chemistry problems. However, these methods come with a caveat - their accuracy cannot be exponentially boosted due to the polynomial scaling of gate counts. Additionally, near-term quantum computers, with their relatively limited number of qubits, aren’t suitable for grid-based strategies.

The discrete basis approach for simulating quantum systems was initially proposed by Abrams and Lloyd in 1997. In this method, the wave function storage necessitates $N⌈log2(M)⌉$ qubits, where $N$ represents the number of electrons and $M$, the count of spin orbitals. The Hamiltonian in this context may contain up to O(N2M6) Pauli terms, which are localized up to $2 log_2(M)$.

The time evolution of the wave function, which maintains correct antisymmetry, is a pivotal subroutine for identifying the ground state of chemical systems. To simulate these systems on a quantum computer, a mapping is needed that converts fermionic operators to qubits. This transformation is executed through encoding methods that transpose the fermionic Fock space into the qubits’ Hilbert space.

One such encoding method is the Jordan-Wigner encoding, which records the occupation number of a spin orbital in the state of a qubit. The fermionic Hamiltonian gets mapped to a linear combination of single-qubit Pauli operators’ products.

Other encoding strategies such as the Hartree-Fock state utilize an antisymmetrized Slater determinant and represent it as a linear combination of basis states. Quantum computers, boasting an edge over their classical counterparts, can store the full configuration interaction wave function using merely $M$ qubits.

Alternatives to the Jordan-Wigner mapping include the parity encoding approach and the Bravyi-Kitaev (BK) encoding. The former stores the parity locally and the occupation number nonlocally. The latter strikes a balance between the locality of the occupation number and parity information. The BK encoding further extends into the BK tree mapping, a generalization of the BK encoding.

Locality preserving mappings, although requiring more qubits than the Jordan-Wigner encoding, have been developed for qubit operators to align with the locality of fermionic Hamiltonians. The Bravyi-Kitaev superfast transform (BKSF) may require fewer gates than the JW mapping due to its unique graph representation of spin orbitals and interaction terms. Furthermore, the BKSF transform has been generalized to lessen the weight of Pauli operators or provide error protection.

Several techniques have been developed to decrease the resources required for quantum chemistry simulations. These include removing qubits using symmetries, low-rank decomposition methods, and Hamiltonian reduction strategies using $\mathbb{Z}_2$ symmetries.

Bravyi and his colleagues developed a method in 2017 that allows the systematic reduction of two qubits using the parity, BK, or BK-tree encoding. This was extended by Setia et al. in 2019 to include molecular point group symmetries.

Low-rank decomposition techniques have proven effective in reducing the cost of time evolution in quantum circuits, as highlighted in McArdle et al.’s 2020 research. Also, Huggins, McClean, et al., in 2019, effectively leveraged this technique to reduce the circuit repetitions required for variational algorithms to locate the ground state energy of chemical systems.

Quantum Computational Chemistry Algorithms

The quantum phase estimation algorithm offers a robust method for determining the lowest energy eigenstate and excited states of a physical Hamiltonian. The process commences by initializing a qubit register, applying a Hadamard gate to each ancillary qubit, and controlling gates to decipher the phase. The necessary ancillary qubits for this phase estimation method are contingent on the desired success probability and precision in the energy estimate.

Enhancements to the basic phase estimation algorithm encompass the utilization of classically obtainable knowledge about the energy gap and entanglement-oriented approaches. Furthermore, preparing the qubit register in a state with a significant overlap with the target eigenstate is vital for quantum computing efficiency.

Adiabatic state preparation (ASP) serves as a method to prepare a state nearing the ground state of a Hamiltonian. This is achieved by gradually transitioning the Hamiltonian from a simplistic form to the target one. The efficiency of ASP largely depends on the gap between the ground state and the first excited state during the transition between the two Hamiltonians.

Another method employed in quantum computing is Trotterization, also known as the “product formula” method. This involves decomposing a time-independent Hamiltonian into local Hamiltonians, and using a first-order Lie-Trotter-Suzuki approximation to simulate time evolution. The accuracy of the simulation hinges on the Trotter formula used, the number of Trotter steps, and the ordering of the terms.

Several alternative methods for the efficient realization of the time evolution operator have emerged, including quantum-walk-based methods, multi-product formulas, Taylor series expansions, Chebyshev polynomial approximations, and qubitization. The cost of these methods correlates to how the Hamiltonian is accessed or “queried” during computation. The linear combinations of unitaries (LCU) query model and sparse Hamiltonians represent two such approaches.

Notably, Taylor series and quantum signal processing with qubitization algorithms have shown remarkable utility in quantum computational chemistry algorithms. These methods exhibit an exponential improvement concerning accuracy compared to product formula-based methods.

Several methods have been leveraged to resolve problems in quantum computational chemistry, including product formulas and advanced Hamiltonian simulation. Gaussian orbital basis sets have been utilized to describe single molecules, leading to a second quantized Hamiltonian with O(M^4) terms.

There have been considerable improvements in phase estimation for molecules in Gaussian basis sets, reducing the scaling from $O(M^{11})$ to $O(M^5)$. Advanced Hamiltonian simulation algorithms, such as qubitization, have contributed to further reductions in asymptotic scaling for chemistry algorithms.

Qubitization has been implemented to create highly efficient algorithms for plane wave and related basis sets. For condensed phase electronic structure problems, this approach shows a gate scaling of $O(M^3)$. Discontinuous Galerkin basis sets provide a more compact description of molecular systems than plane waves, which further reduces the scaling of qubitization to around $O(M^{2.6})$.

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm is instrumental in finding the lowest eigenvalue of a given Hamiltonian, such as that of a chemical system, using a hybrid quantum-classical approach. The algorithm is grounded on the Rayleigh-Ritz variational principle and leverages a parametrized trial wave function to discover the ground state wave function and energy.

Despite its potential, the VQE algorithm presents challenges including its heuristic nature and the substantial number of measurements required. Considerations such as hardware compatibility and appropriate Ansatz selection are crucial in achieving its goals.

There are two types of Ansätze: hardware-efficient and chemically inspired. While the former are suitable for small systems, they do not scale well for larger ones due to the complexity of classical optimization. Chemically inspired Ansätze adapt classical computational chemistry algorithms for quantum computers, bridging the gap between classical and quantum computational chemistry.

While quantum computing provides exciting avenues for progress in computational chemistry, it is important to acknowledge the difficulties in its application. Realistic noise has rarely been considered in optimization studies, leaving a degree of uncertainty about the effectiveness of each method. As near-term quantum computers may not have enough physical qubits for error correction, the development of alternative methods for near-future chemistry simulation is paramount.

Despite these hurdles, numerous methods have been proposed to facilitate classical optimization in quantum computing. These range from using quantum circuits to calculate analytic gradients, to applying adiabatic quantum computing concepts. The quantum subspace expansion (QSE) method proves useful in near-term quantum computational chemistry for finding excited states and refining ground state estimation.

Error Mitigation for Chemistry

Quantum error correction plays a crucial role in minimizing computation errors. However, its implementation is far from straightforward as it demands a significant augmentation in the number of qubits deployed. Furthermore, as beneficial as quantum error correction is, it’s not a standalone solution. For complex calculations, particularly in the realm of chemistry which are conventionally intractable, supplementary strategies become essential.

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) stands out as a more suitable contender for noisy quantum hardware, owing to its diminished coherence time requirements. Yet, without quantum error correction, it falls short in tackling classically intractable chemistry calculations.

Error mitigation techniques strive to approximate the flawless measurement result from a noise-impacted one, provided the error rate remains within manageable limits. However, it’s crucial to recognize that scalable solutions call for fault-tolerant, error-corrected quantum computers.

A novel approach, the extrapolation method, strategically elevates the error rate to infer an error-free result via extrapolation. Techniques grounded in Richardson extrapolation are commonly employed here. Exponential extrapolation, specifically, emerges as an apt technique for large quantum circuits. This methodology has proven its efficacy in VQE experiments within molecular chemistry and nuclear physics.

Probabilistic error cancellation is another unique technique that annuls errors by simulating the reverse of an error channel. This method concentrates on measurement outcomes and corrects the impact of the unphysical inverse channel on the expectation value. Additionally, it demonstrates flexibility and adaptability as it can be extended to multiqubit gates, successfully combating general Markovian noise and temporally correlated errors.

Implementing these techniques necessitates comprehensive knowledge of the noise model related to each gate. This data can be sourced from either process or gate set tomography.

A groundbreaking development is the Quantum Subspace Expansion (QSE), which can rectify errors in the VQE and calculate excited energy eigenstates. QSE quantifies the matrix representation of the Hamiltonian in a subspace and resolves a generalized eigenvalue problem to yield the error mitigated spectrum of the Hamiltonian. A two-qubit superconducting system experimentally demonstrated QSE’s capability to measure the ground and excited state energies of $H_2$.

Symmetry-based methods present another pathway to mitigating errors in VQE, through checks on conserved quantities like the electron number or s z value. This category encompasses techniques such as stabilizer checks, physically derived constraints, low-rank and orbital rotations measurement technique, and introducing additional symmetries through fermion-to-qubit mapping.

A notable contribution in this field is from McClean, Jiang et al. (2020), who advanced an extension of quantum subspace expansion. This extension integrates additional symmetries into the system using an error-correcting code to detect and correct errors.

In the pursuit of flawless quantum chemistry calculations, numerous error mitigation methods have been proposed. These include the quantum variational error corrector and individual error reduction. Despite the strides made, further research remains pivotal to determine the true efficacy of these techniques.

Illustrative Examples

Taking hydrogen (H2) and lithium hydride (LiH) as examples, they delve into the crux of quantum chemistry. The significance of employing extensive basis sets for precise results is emphasized, particularly when dealing with these elementary molecules.

The precision of quantum computation hinges on the discrete function set used to simulate the molecule’s spin orbitals. With an increased orbital count, this edge closer to a genuine estimation of the ground state energy. The four spin orbitals employed for H2 under the STO-3G basis—each hydrogen atom using one—is a testament to this method’s effectiveness.

In quantum computations, the Hamiltonian problem is effectively transformed into qubit operators via the Jordan-Wigner (JW) encoding, resulting in a four-qubit Hamiltonian for H2. This JW encoding simplifies the construction of the Hartree-Fock (HF) state for the H2 molecule.

An accurate description of the H2 molecule’s ground state at equilibrium bond distance can be achieved through a mean-field solution. Furthermore, the unitary coupled-cluster with single and double excitations (UCCSD) Ansatz for H2 is both derivable and simplified using techniques such as Trotterization and basis rotations.

The 6-31G basis set for H2 presents a double-zeta representation of valence electrons, resulting in eight spin orbitals for consideration. Moreover, Bravyi-Kitaev (BK) encoded states for 6-31G H2 can be assembled using the BK transformation matrix, even for an eight spin-orbital system.

Quantum computational chemistry leverages specific functions to map fermionic orbitals to qubits. For example, in the case of the STO-3G basis for LiH, the system of 12 spin orbitals can be compacted into a six-qubit form. Additionally, the BK-tree mapping technique eliminates the qubits related to conservation symmetries, leading to a six-qubit final Hamiltonian with a minimal energy discrepancy from the complete 12-qubit Hamiltonian.

While classical methods fluctuate in terms of cost and accuracy, quantum computers show potential for systems with about 100-200 spin orbitals that require high-precision calculations. Quantum computers also exhibit capacity for storing full configuration interaction (FCI) wave functions using M qubits, although error correction significantly increases the qubit overhead.

Despite advancements, the realization of quantum computers capable of implementing complex algorithms might still be years away. The first quantum computer generations will likely be substantially smaller than the estimated 100,000 physical qubits needed for quantum error correction. Further research is required to validate whether the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) approach can enable small quantum computers with 100-200 physical qubits to outshine classical methods.

A potential solution for overcoming these challenges is to use known chemistry calculations as quantum technology benchmarks. Quantum methods face obstacles due to high error rates and low qubit counts of existing hardware, and further work is needed to compile existing proposals and identify those most suitable for near-term hardware.

Reference

- McArdle, S., Endo, S., Aspuru-Guzik, A., Benjamin, S. C. & Yuan, X. Quantum computational chemistry. Reviews of Modern Physics 92, (2020).

Leave a comment