This review is written by non-expert and used for personal study only.

Three types of incremental learning

- Learning Algorithm

Introduction to Continual Learning

Deep learning faces challenges when learning incrementally from constantly changing data, which can lead to catastrophic forgetting – a situation where the model loses previously learned information. Continual learning research aims to overcome this limitation and bring artificial intelligence closer to natural intelligence. However, a shared framework is missing in this field, making it difficult to compare algorithms systematically. To tackle this issue, a clear and intuitive framework is proposed.

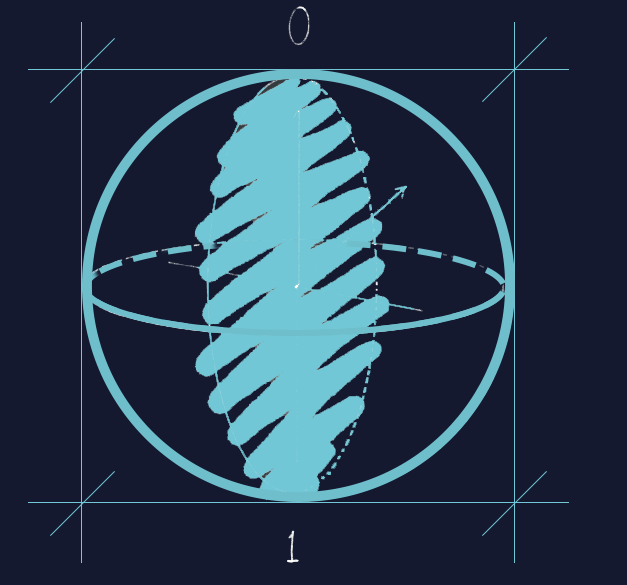

Scenarios in Supervised Continual Learning

This paper presents three main scenarios for supervised continual learning: task-incremental, domain-incremental, and class-incremental learning. Each scenario has its unique challenges. The scenarios are described intuitively before being formally defined based on how the aspect of data that changes over time relates to the function or mapping that must be learned. Task-incremental learning involves learning separate tasks with distinct identities, while domain-incremental learning deals with tasks that have the same possible outcomes but with changing context or input-distribution. Class-incremental learning requires an algorithm to learn to differentiate between an increasing number of objects or classes in a series of classification-based tasks.

Contexts and Adaptable Approaches

The article discusses three scenarios in the context of continual learning, where a classification problem is divided into multiple non-overlapping contexts to be learned sequentially. Each scenario is defined based on how the function or mapping to be learned relates to the context space. The term “task” is deemed problematic, and the article suggests using “context” instead.

By distinguishing between ‘context set’ and ‘data stream,’ the article introduces a more adaptable approach for continual learning problems with gradual transitions or revisited contexts. The context set describes the aspects of the data that can change over time, while the data stream is a sequence of experiences presented to the algorithm.

Methods and Performance in Continual Learning Scenarios

The paper discusses various methods for incorporating context-specific components in neural networks, such as context-dependent gating and separate networks approach, as well as regularization methods like elastic weight consolidation and synaptic intelligence. An empirical comparison of different continual learning methods was conducted using Split MNIST and Split CIFAR-100 protocols, and the performance of these methods in task-incremental, domain-incremental, and class-incremental learning scenarios was reported. Replay-based methods performed relatively well in all scenarios, while template-based classification also showed promise in class-incremental learning.

The article addresses the challenges of continual learning in deep neural networks and the lack of structure in the field. It proposes three scenarios for continual learning, providing a foundation for defining benchmark problems that can help bridge the gap between natural and artificial intelligence. The article demonstrates that replay, either with data sampled from a memory buffer or a generative model, is the only strategy among the top performers in all three scenarios. Regularization-based strategies fall short in class-incremental learning, highlighting the importance of replay or template-based classification for success in this scenario.

Required Additional Study Materials

- Hadsell, R., Rao, D., Rusu, A. A. & Pascanu, R. Embracing change: continual learning in deep neural networks. Trends Cognit. Sci. 24, 1028–1040 (2020).

- French, R. M. Catastrophic forgetting in connectionist networks. Trends Cognit. Sci. 3, 128–135 (1999).

- Marr, D. Vision: A computational investigation into the human representation and processing of visual information (WH Freeman, 1982).

- Belouadah, E., Popescu, A. & Kanellos, I. A comprehensive study of class incremental learning algorithms for visual tasks. Neural Networks 135, 38–54 (2021).

- Jin, X., Sadhu, A., Du, J. & Ren, X. Gradient-based editing of memory examples for online task-free continual learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 34, 29193–29205 (2021).

Introductory material

- “Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning” by Christopher Bishop

- “The Elements of Statistical Learning” by Trevor Hastie, Robert Tibshirani, and Jerome Friedman

- “Deep Learning” by Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville

- “Neural Networks and Deep Learning” by Michael Nielsen

Reference

van de Ven, G.M., Tuytelaars, T. & Tolias, A.S. Three types of incremental learning. Nat Mach Intell 4, 1185–1197 (2022).

Deep transfer operator learning for partial differential equations under conditional shift

- Applied Mathematics

Introduction to Transfer Learning and Challenges in Deep Learning Models

This article discusses the challenges faced when there is a limited amount of labeled data available for training deep learning models in the context of complex physical processes. These processes are governed by mathematical equations called partial differential equations (PDEs). To overcome this issue, the authors suggest using a technique called transfer learning (TL). TL involves using a model that has already been trained on one domain, with sufficient labeled data, and adapting it for a related domain where only a small amount of training data exists. This method has been successfully used in various machine learning problems, and its effectiveness depends on the similarities between the source and target data.

TL-DeepONet Framework for Transfer Learning under Conditional Shift

The article introduces a novel framework called TL-DeepONet for transfer learning under conditional shift, which means when the data distribution changes, using a type of model called neural operators. The framework first trains a model (source model) on a domain with ample labeled data and then transfers the learned information to another model (target model) trained on a domain with very limited labeled data. A special loss function, called the hybrid loss function, is used to measure the differences between the data distributions in the two domains.

Leveraging Domain-Invariant Features for Efficient Initialization

The TL-DeepONet framework takes advantage of features that are common across the two domains, extracted by the source model, to efficiently initialize the target model’s variables. This allows for the identification of the PDE operator in domains where there is limited labeled data available. The framework is demonstrated on various transfer learning problems involving parametric PDEs, which are PDEs with parameters that can be changed. Examples include changes in the shape of the domain, the dynamics of the model, the properties of materials, and nonlinearities in the model.

Application of TL-DeepONet to Real-World Problems

The article focuses on the TL-DeepONet framework for transfer learning problems that involve adapting a model trained on one domain to work effectively on another domain with different data distributions. This framework is designed to help efficiently initialize the target model using features common to both domains, extracted by the source model. The authors provide examples of different transfer learning problems in PDEs, such as simulating fluid flow in hydrology and hydrogeology, to demonstrate the effectiveness of the approach.

The article presents a novel transfer learning framework that uses neural operators to address the challenges posed by limited labeled data when training deep learning models for complex physical processes governed by PDEs. The proposed TL-DeepONet framework allows for efficient and accurate learning, even when limited labeled data are available. This is particularly useful in various real-world applications where collecting and labeling data can be expensive or time-consuming.

Required Additional Study Materials

- Zhuang, F. et al. A comprehensive survey on transfer learning. IEEE 109, 43–76 (2020).

Introductory material

- “Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning” by Christopher Bishop

- “The Elements of Statistical Learning” by Trevor Hastie, Robert Tibshirani, and Jerome Friedman

- “Deep Learning” by Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville

- “Neural Networks and Deep Learning” by Michael Nielsen

- “Partial Differential Equations: An Introduction” by Walter A. Strauss

- “Partial Differential Equations for Scientists and Engineers” by Stanley J. Farlow

Reference

Goswami, S., Kontolati, K., Shields, M.D. et al. Deep transfer operator learning for partial differential equations under conditional shift. Nat Mach Intell 4, 1155–1164 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-022-00569-2

Data-driven discovery of intrinsic dynamics

- Scientific Data

Introduction to Dynamical Models and the Proposed Method

The text discusses the significance of dynamical models in understanding systems and predicting their future behavior. These models are essential for studying various natural systems and how they evolve over time. However, deriving high-dimensional dynamical models can be challenging due to the complexity involved. The paper introduces a method that aims to learn low-dimensional deterministic dynamical models directly from time-series data, making it easier to analyze and predict system behavior.

To simplify the concept, consider a system with multiple variables that change over time. These variables form a high-dimensional space where each point represents a state of the system. The challenge is to find a simpler, low-dimensional representation that can still accurately describe the system’s behavior. The proposed method assumes that the data lies on or near a low-dimensional manifold (a smooth, curved surface) in the high-dimensional state space. To learn this manifold, nonlinear manifold learning techniques are employed, which are capable of capturing the complex relationships between variables in the system.

Methodology: Manifold Learning and Neural Networks

The paper introduces a novel method for learning minimal-dimensional dynamical models directly from data. This method combines mathematical theory and neural networks to analyze the high-dimensional state space of a system. It starts by breaking down the manifold into overlapping patches, which are then reduced to their intrinsic dimensionality (the simplest representation) using autoencoders. Autoencoders are a type of neural network that learn to compress data while retaining essential information. The dynamics within each patch are learned using separate neural networks, which helps in understanding how the system behaves locally.

Once the dynamics of each patch are learned, they are combined or “sewn” together to form a global dynamical model. This approach does not require a global parameterization of the manifold, meaning that the overall structure of the manifold does not need to be known beforehand. The method’s strength lies in its ability to reduce data to the intrinsic dimensionality of the nonlinear manifold without losing crucial information.

The paper describes a method for learning minimal-dimensional dynamical models directly from data using neural networks. To help understand this process, imagine a complex, high-dimensional system as a landscape with mountains, valleys, and plateaus. The method starts by dividing this landscape into overlapping regions or patches. Each patch is then simplified into a more manageable, low-dimensional representation using autoencoders. This step is similar to creating a local map of each region. The dynamics or the way the system changes over time within each patch are learned using neural networks, which act like a set of rules describing how the system behaves within that region.

Creating a Global Dynamical Model

After understanding the dynamics of each patch, the local maps are combined to create a global dynamical model representing the entire landscape. This is achieved without needing a global parameterization of the manifold, which would be like creating a single, unified map of the entire landscape. The method aims to learn these manifolds and the dynamics on them directly from data, without making any assumptions about the underlying system.

The article presents a new method for learning minimal-dimensional dynamical models directly from data, combining the mathematical theory of manifolds with the approximation capabilities of neural networks. This approach is based on learning an atlas of charts, where each chart represents the local coordinates of a patch of the manifold. The dynamics are learned on each patch using neural networks, which can then be patched together to create a global dynamical model without needing a global parameterization of the manifold.

To illustrate the method, consider a simple example of a particle moving around a unit circle at a constant speed. The method can accurately model this system and can also handle more complex examples, as discussed in the “Examples” section. By using this approach, it is possible to analyze and predict the behavior of various systems, even those with high-dimensional data, making it a valuable tool for studying complex natural phenomena.

In the paper, the authors propose a method for learning minimal-dimensional dynamical models directly from data by integrating the mathematical theory of manifolds with the approximation capabilities of neural networks. The approach consists of two main steps: first, learning an atlas of charts; and second, learning the dynamics within the local coordinates of each chart, and then combining these local descriptions to form a global representation.

To better understand this process, consider the data manifold as a complex, curved surface in a high-dimensional space. The first step involves decomposing the manifold into overlapping patches using k-means clustering, a technique that partitions the data into disjoint sets. These sets are then used to create a graph, which in turn helps to expand each cluster along the graph, forming overlapping coordinate domains. Autoencoders, a type of neural network, are employed to learn the coordinate maps and their inverses for each patch.

The second step involves learning the dynamics of the system by approximating the maps in the local coordinates of each chart using neural networks. Once the dynamics are learned, the method enables a seamless transition between charts to form a global dynamical model. This approach is tested on several examples with increasing complexity, such as a simple periodic orbit in a plane, the complex bursting dynamics of the Kuramoto-Sivashinsky equation, and others. The results demonstrate the method’s accuracy and ability to produce seamless transitions between charts.

The text further explains a new method for learning dynamical models directly from data, which is based on the theory of manifolds and the approximation capabilities of neural networks. By decomposing the data into overlapping patches and reducing each patch to its intrinsic dimensionality using autoencoders, the dynamics of each patch are learned using neural networks. This process allows for the construction of a global dynamical model without the need for a global parameterization of the manifold.

Applications, Results, and Future Research

This method has been tested on several examples of increasing complexity, including a simple periodic orbit in the plane, quasiperiodic dynamics on a torus, and a reaction-diffusion system. The results indicate that the method is effective in reducing the dimension of the system to its intrinsic dimensionality, producing a minimal dynamical model for high-dimensional data.

The authors have developed a powerful method for learning minimal-dimensional dynamical models directly from high-dimensional time-series data. By finding and parameterizing the low-dimensional manifold on which the data reside and then learning the dynamics on that manifold, the method can learn accurate dynamical models whose dimension matches the intrinsic dimensionality of the system. This approach outperforms single-chart methods and offers a promising new direction for the study of complex systems in physics and other disciplines.

The authors also suggest that tools from graph theory and topological data analysis could provide guidance in choosing the optimal number of charts for a given dataset, which is an area for future research. This novel method stands apart from other recently developed techniques, such as those based on Koopman operator theory and reservoir computing, which rely on high-dimensional state representations. The method presented in this paper offers valuable insights for understanding and predicting the behavior of a wide range of complex systems.

Required Additional Study Materials

- Doering, C. R. & Gibbon, J. D. Applied Analysis of the Navier-Stokes Equations Cambridge Texts in Applied Mathematics No. 12 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1995)

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y. & Courville, A. Deep Learning (MIT Press, 2016).

- Ma, Y. & Fu, Y. Manifold Learning Theory and Applications Vol. 434 (CRC, 2012)

- Lee, J. M. Introduction to Smooth Manifolds (Springer, 2013)

Introductory material

- “Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning” by Christopher Bishop

- “The Elements of Statistical Learning” by Trevor Hastie, Robert Tibshirani, and Jerome Friedman

- “Deep Learning” by Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville

- “Neural Networks and Deep Learning” by Michael Nielsen

- “Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos” by Steven H. Strogatz

- “Differential Equations, Dynamical Systems, and an Introduction to Chaos” by Morris W. Hirsch, Stephen Smale, and Robert L. Devaney

Reference

Floryan, D., Graham, M.D. Data-driven discovery of intrinsic dynamics. Nat Mach Intell 4, 1113–1120 (2022).

Large-scale chemical language representations capture molecular structure and properties

- Method Development

Introduction to Machine Learning for Molecular Property Prediction

The text explores the application of machine learning (ML) in predicting molecular properties, a task that is vital in fields such as drug discovery and materials design. To understand and predict these properties, scientists often rely on chemical descriptors, which are a set of values that provide information about the molecules’ characteristics. Recently, advanced models have shifted their focus to automatically learning these features from molecular graphs or line notations, such as the Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES). SMILES is a way of representing the structure of a chemical compound using ASCII strings, making it easier for computers to process.

However, the SMILES notation system can be complex and limiting, leading researchers to develop alternative representations like SMARTS and SELFIES. String-based representations have been utilized in predicting molecular properties, but graph neural networks (GNNs) have generally outperformed them due to their ability to consider the topological structure of molecular graphs. In simple terms, GNNs take into account the arrangement of atoms and bonds within a molecule, which is crucial for understanding its properties.

MoLFormer Model Development

The article highlights the challenges associated with predicting molecular properties using machine learning, such as the scarcity of labeled data and the limitations of current molecular representations. It points out the success of pretraining language models and graph neural networks on large unlabeled datasets in other domains and suggests extending this approach to molecular property prediction. However, the capability of these pretraining models to capture molecule-property relationships across various tasks remains unexplored.

To address this challenge, the authors present the development of molecular language transformer models (MoLFormer). These models are trained on over a billion molecules using an efficient linear time attention mechanism, which is a technique that helps the model focus on relevant parts of the input data while processing it. The MoLFormers show competitive performance in predicting a wide range of molecular properties, including those derived from quantum mechanics, and demonstrate the ability to capture substructures and spatial interatomic distances from SMILES annotations alone. This means that MoLFormers can accurately represent and learn about the chemical and structural information of molecules, outperforming or matching the best graph neural networks.

MoLFormer Model Performance

The MoLFormer model is based on a masked language model framework, a technique that allows the model to learn from large-scale chemical SMILES data by predicting parts of the input data that are intentionally hidden. The model is trained on over a billion molecules using efficient linear time attention and adaptive bucketing of batches, a method that helps to speed up the training process. The results show that the pretrained MoLFormer performs competitively with existing supervised or unsupervised language model and graph neural network baselines in predicting a wide variety of molecular properties, including quantum-mechanical properties.

To derive MoLFormer embeddings, which are numerical representations of the molecules, the authors encode a chemical SMILES by taking the mean of all embeddings of the last hidden state from the encoder model. These embeddings are then used for downstream tasks, which are divided into two categories: frozen and fine-tuned. In the frozen setting, a fully connected model is trained for each task while keeping the encoder embeddings fixed. In the fine-tuned setting, the weights of the encoder model are fine-tuned jointly with the fully connected model for each downstream task. A two-layer fully connected network with a hidden dimension of 768 and Gaussian error linear unit layers is used for the fine-tuned strategy.

Ablation Studies and Conclusion

The authors present MoLFormer, a molecular SMILES transformer model that is pretrained on a large corpus of 1.1 billion molecules using an efficient linear attention mechanism. This model is specifically designed to predict molecular properties from SMILES strings. To ensure that the model performs well, the authors evaluate it on several classification and regression tasks from ten benchmark datasets, covering quantum-mechanical, physical, biophysical, and physiological property prediction of small-molecule chemicals from MoleculeNet. MoleculeNet is a collection of datasets used for molecular property prediction, providing a standard benchmark for evaluating new methods in this field.

The performance of MoLFormer embeddings is compared with existing baselines on six classification and five regression tasks from the MoleculeNet benchmark. The results show that MoLFormer representations can accurately capture sufficient chemical and structural information to predict a diverse range of chemical properties. In fact, MoLFormer outperforms or performs similarly to existing graph neural network (GNN) baselines on several classification and regression tasks. This indicates that MoLFormer is an effective model for capturing sufficient chemical and structural information for predicting various chemical properties.

The authors evaluate the performance of a larger version of MoLFormer, called MoLFormer-XL, on six classification and five regression tasks from the MoleculeNet benchmark. They compare its performance with existing baselines and report that MoLFormer-XL outperforms all baselines in three out of six classification benchmarks and comes close to the top in the other three. In regression tasks, MoLFormer-XL outperforms the existing supervised GNN baselines on all five tasks. These results confirm the model’s generalizability and its ability to perform well across a variety of molecular property prediction tasks.

The study also explores the effectiveness of pretrained chemical language models in predicting a broad range of downstream molecular properties from quantum chemical to physiological, using only SMILES annotations. This is particularly important because it shows that the model can learn and predict molecular properties without requiring additional information, such as 3D structures, which can be computationally expensive to obtain.

To better understand the factors contributing to the impressive performance of MoLFormer-XL, the authors conduct ablation studies, which involve removing certain components or varying certain parameters of the model to see their impact on performance. These ablation studies are divided into three categories: (1) the impact of pretraining data size, nature, and model depth, (2) the results with and without fine-tuning the model on downstream data, and (3) the effect of using absolute versus rotary positional embeddings.

The ablation study results provide insights into the neural and data scaling behavior of MoLFormer. For instance, the model pretrained on larger datasets performs better than models pretrained on smaller datasets. Fine-tuning the model on downstream data also achieves better performance across all pretraining dataset sizes, indicating that this technique is beneficial for improving the model’s predictive capabilities.

Overall, this research presents MoLFormer, a large-scale pretrained molecular language model capable of predicting molecular properties from SMILES sequences. The model outperforms existing graph-based baselines on various molecular regression and classification benchmarks, demonstrating its potential in fields such as drug discovery and material design. Furthermore, the model is efficient and environmentally friendly, requiring significantly fewer GPUs for training compared to other methods. The authors emphasize the potential of MoLFormer in various applications, but they also call for responsible use and validation of the technology to ensure its effectiveness and reliability in real-world scenarios.

Required Additional Study Materials

Introductory material

- “Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning” by Christopher Bishop

- “The Elements of Statistical Learning” by Trevor Hastie, Robert Tibshirani, and Jerome Friedman

- “Deep Learning” by Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville

- “Neural Networks and Deep Learning” by Michael Nielsen

- “Chemistry: The Central Science” by Theodore L. Brown, H. Eugene LeMay Jr., Bruce E. Bursten, Catherine Murphy, Patrick Woodward, and Matthew E. Stoltzfus

- “Organic Chemistry” by Paula Yurkanis Bruice

Reference

Ross, J., Belgodere, B., Chenthamarakshan, V. et al. Large-scale chemical language representations capture molecular structure and properties. Nat Mach Intell 4, 1256–1264 (2022).

Leave a comment